Photographer: Donna Foster Roizen. Copyright holder: Frederic Jueneman. Available in the Wikimedia Commons. Velikovsky at the 1974 AAAS Meeting in San Francisco.

Find the corresponding podcast episode here: Initial Conditions - A Physics History Podcast

It’s easy to think of science as a process that moves through the will of a handful of brilliant, driven, geniuses. As a reader of Ex Libris Universum, of course, you know that this is an extreme simplification. Regardless, the story of the genius figure has staying power, no doubt because that is how most people learn about the subject. Take, as some examples, Einstein and relativity, Newton and gravity, Galileo and heliocentrism. Despite what this common narrative tells us, science is a social process. From education and training to publication in peer reviewed journals, science requires scientists to participate in a community. That is one of the most fundamental aspects of how new scientific knowledge is generated. In this episode, we discuss a number of individuals who came up with some interesting ideas that could not stand up to the rigorous scientific process, nor pass muster among established scientists.

Before I begin, I should point out that my insights here aren’t particularly original. This episode was based on the research of Michael Gordin, a historian of science at Princeton University. Gordin has published two monographs on the topic of pseudoscience and fringe theories. In The Pseudoscience Wars: Immanuel Velikovsky and the Birth of the Modern Fringe (University of Chicago Press, 2012), Gordin argues that pseudoscience is a negative category. It has been used by scientists at different times to discredit unorthodox or antithetical ideas outside of mainstream science. In this episode, we use Gordin’s ideas about pseudoscience and the scientific fringe to figure out why the scientific community matters in the legitimization of scientific knowledge. Check out the bibliography below to see some of Gordin’s writing about the scientific fringe.

While researching this episode in the Niels Bohr Library & Archives, I came across the Alex Harvey Collection on Crank Theories. The name struck me as odd, so I decided to request the materials. Harvey, the former Chair of the Department of Physics at Queens College in New York City, collected about two dozen pseudoscientific tracts, which he later donated to the Niels Bohr Library & Archives. They ranged in quality from bizarre pamphlets to bound monographs indistinguishable from legitimate scientific books (except for numerous typos–vanity presses, which accept fees from authors seeking to publish their books–seem to have low standards for copy editing). On some of the manuscripts Harvey attached post-it notes with instructions such as “crank theory—throw away.” For some reason, he ignored his own advice, ultimately leaving NBL&A with this very unusual collection.

I don’t know the exact reason why these fringe thinkers sent their manuscripts to Harvey. I can speculate that the authors sought approval from the community of legitimate scientists. If their ideas were so revolutionary, or simple, or obvious, they might have thought, then actual, practicing scientists should have no problem seeing the merits of their arguments and supporting their conclusions. Although many of the pseudoscientists included in the Harvey collection had big egos—one must have tremendous conviction to brazenly buck long established theories—they still likely recognized the social dimension of scientific research and the role the community plays in legitimizing knowledge.

By seeking comments from an established physicist, the fringe scientists in the Harvey collection were following in the footsteps of Immanuel Velikovsky, perhaps the leading pseudoscientist of the mid-twentieth century. Velikovsky was once a household name; his first book Worlds in Collision

Photographer: Donna Foster Roizen. Copyright holder: Frederic Jueneman. Available in the Wikimedia Commons. Velikovsky at the 1974 AAAS Meeting in San Francisco.

You’re not alone in thinking that the arguments Velikovsky laid out in Worlds in Collision sound strange. Initially, Velikovsky tried to garner interest in his catastrophism by mailing copies of his manuscript to scientists and librarians, receiving few responses. After many rejections from publishing houses, Velikovsky received an acceptance from Macmillan, a well-regarded publisher of academic textbooks. When Macmillan announced the publication details, scientists responded vociferously against the book, criticizing Velikovsky’s tenuous grasp on basic astronomy and physics. Edward Thorndike, Alex Harvey’s predecessor at Queens College, was one of the first reviewers. Of Worlds in Collision he wrote “the physics are not good.”

Instead of dissuading him, scientists’ response to his book made Velikovsky a celebrity and boosted sales of his debut book. While scientists were able to convince Macmillan to cancel publication of Velikovsky’s book, the contract was picked up by Doubleday, which soon had a bestseller on its hands. Gordin goes on to describe how Velikovsky capitalized on the counterculture and its rejection of establishment science, eventually creating peer reviewed journals and courses of study for Velikovskianism that paralleled mainstream scientific practices. As Velikovsky continued to publish his ideas about cosmological catastrophes, scientists loudly denounced his research as pseudoscience, which allowed Velikovsky to present himself as a besieged crusader for truth. Things came to a head at the 1974 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, during which the conference organizers scheduled a meeting where Velikovsky himself discussed his work with scientists like Carl Sagan. The meeting was first conceived in 1972, after Walter Orr Roberts, a former president of the AAAS, suggested a symposium to bring together astronomers and Velikovskians after reading the first issue of Pensée, Velikovsky’s journal. Neither side left the meeting convinced of the other’s conclusions, but the scientists could at least argue that they gave Velikovsky a fair shake.

Like Velikovsky, the authors included in the Harvey collection had strong personalities that show through their writing. They were, for the most part, convinced of their own brilliance in the face of the scientific consensus. Most of the authors whose work is in the collection dispute the accuracy of Einstein’s theory of relativity. They often make their arguments in language that sounds scientific and could pass for legitimate science to uninformed readers. The writers included in the Harvey collection point to the appeal of scientific validation. The fringe thinkers understand that even if scientists have been wrong about Einstein (and therefore much of physics in the twentieth century), they remain the arbiters of what constitutes scientific fact and pseudoscientific fiction. Pseudoscientists cannot add to or challenge scientific facts if legitimate scientists are unwilling to consider their work. The force of one personality cannot sustain pseudoscientific ideas. Velikovsky relished the attention. He was, after all, a brilliant self-promoter. Velikovsky likely viewed the 1974 meeting and scientists’ decades-long campaign against his work as indicating that Worlds in Collision was a subversive and powerful challenge to established scientific knowledge and tradition. Yet throughout his life he also sought out the company of scientists who would listen to him. In 1952 Velikovsky moved to Princeton, New Jersey, where he struck up a friendship with Albert Einstein. The two Jewish emigres likely bonded over their shared background. At times, Velikovsky asked Einstein to look over his research. Early in his career he was genuinely interested in having scientists legitimize his arguments, but his stubborn personality blinded him to constructive criticism.

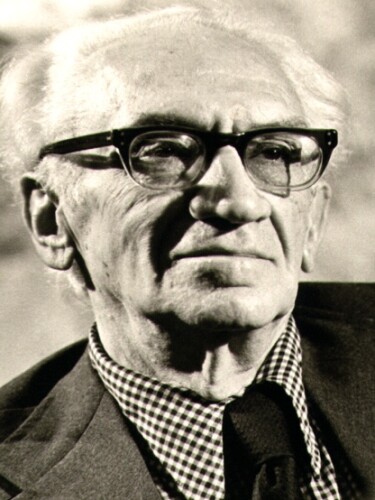

The story of Ralph Hartley (1888-1970) also shows how blurry the line between pseudoscience and science can be, and how legitimate scientific knowledge is determined through the community, rather than by lone practitioners. Hartley was an electronics researcher who laid much of the groundwork for the field that would later be known as information theory. Most of his career was spent working for Bell Laboratories. Apart from his work with electronics, Hartley had a lifelong interest in the theory of relativity. More specifically, Hartley—like many of the writers in the Harvey collection—thought that Einstein was wrong and that Maxwell’s equations were sufficient for explaining the propagation of electromagnetic waves. To do so, Hartley argued that there was a dissipationless liquid that comprised the emptiness between objects in space. It was another term for the aether that had been used for much of the nineteenth century. By Hartley’s time, the aether theory had fallen out of favor as the 1887 Michelson-Morley experiment and improved observations of the universe pointed to its inaccuracy.

Ether-Drift Interferometer, as used by Morley and Miller in 1903-1905. An earlier version of this device that was used in the 1887 Michelson-Morely experiment detected no drag on the propagation of light waves from the aether, dealing a blow to the theory which had been dominant for much of the 19th century.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

Portrait of Herbert Ives.

Bell Laboratories / Alcatel-Lucent USA Inc., courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Hartley spent decades trying to publish his arguments in scientific journals. He had some allies, most notably Herbert Ives, but he was unsuccessful in getting his theories published in journals of distinction. Two reviewers assigned to a draft that Hartley submitted to The Physical Review in 1953 summed up the scientific community’s response to his ideas. The first reviewer wrote: “I would not advise The Physical Review to reopen now a discussion on relativity, especially when the alternative theory proposed in this paper remains so vague and imprecise. The author proposes an incompressible non-linear ether. This means an infinite velocity of propagation for longitudinal waves, which has never been observed—and the non-linearity has never been observed either.” The second review was even more forceful in its rejection: “These articles do not warrant publication in The Physical Review. The author, misunderstanding results of [Herbert] Ives’s campaign against the Lorentz transformation and the special theory of relativity, mistakenly argues we must return to classical mechanics for a relativity principle. He therefore seeks a classical system capable of propagating wave motion in accordance with Maxwell’s equations, and comes up with Kelvin’s gyroscopic model of MacCullagh’s 1839 ether. That some of the properties of his solutions mimic the behavior of objects in the special theory of relativity is hence not surprising, as they follow from Maxwell’s equations. Thus, based on a misunderstanding nurtured by Ive’s [sic] stubborn fight against Lorentz and Einstein, the author proposes a step which would throw theoretical physics well back into the past century.”

Hartley was not dissuaded by journal editors’ reluctance to publish his ideas. He eventually had a paper published in the October 1959 issue of Philosophy of Science. The journal name suggests that its editors were more willing to accept papers that ran against the grain of mainstream science. After his article was published, Hartley found some supporters around the world who were also skeptical of Einsteinian relativity. Still, he had trouble getting his subsequent research on the aether into scientific journals. Never a healthy man, Hartley suffered from what he called “nerve exhaustion” which kept him bedridden and recuperating for months. Despite his ailment, he continued his research until his death in 1970.

The scientific community plays the decisive role in determining what is or is not science. Velikovsky was able to build some parallel institutions that resembled those of legitimate science, but after his death his followers struggled to maintain the momentum that Velikovsky himself brought to his field of study. In Hartley’s case, the peer review process worked as intended to make sure that his reversion to the outdated aether theory did not gain traction in the scientific mainstream. Publishing Hartley’s ideas would lend them credibility which could in turn damage the reputation of legitimate science. The form that science takes—its language, methodologies, and editorial processes—is quite appealing to pseudoscientists. Yet, by the same token, ideas that are too outlandish rarely make it very far along in mainstream scientific institutions. The purpose of focusing on pseudoscientists is not to make light of their efforts, but rather to highlight the important role that the social practice of science plays in generating legitimate, verifiable, and accurate knowledge about the natural world.

You can listen to Initial Conditions: A Physics History Podcast wherever you get your podcasts. A new episode will be released every Thursday so be sure to subscribe! On our website

Bibliography

Gordin, Michael D. On the Fringe: Where Science Meets Pseudoscience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Gordin, Michael D. The Pseudoscience Wars: Immanuel Velikovsky and the Birth of the Modern Fringe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Subscribe to Ex Libris Universum

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month