Because there is no known photograph of Foote, we rely on artist illustrations such as this action shot of a woman scientist by Carlyn Iverson.

Carlyn Iverson

Find the corresponding podcast episode here: Initial Conditions - A Physics History Podcast

Welcome to the first ever episode of Initial Conditions: A Physics History Podcast and its accompanying blog post! This show has been many months in the making and I am so excited to share it! I am even more excited that our first episode is one that is so close to my heart: the story of Eunice Foote (1819-1888), the once forgotten pioneer of climate science. In these blog posts, Justin and I will share how we made each episode and the details that did not make it into the show (the most difficult part of each episode is deciding what to cut). These posts are meant to extend the episode to make the research process accessible, share our favorite resources, and encourage further learning and exploration.

If you want to know the story of humans studying climate change, you need to know the story of Eunice Foote. In 1856, Eunice Foote, an American amatuer scientist, conducted an experiment on the effect of the sun’s heat on different atmospheric conditions. She concluded that increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would lead to a warmer planet. To reach this conclusion, Foote isolated different gasses and atmospheric conditions in glass jars. She then exposed them to sunlight, measuring the temperature every few minutes. She found water vapor absorbed and retained heat well, but the most effective gas was carbon dioxide. She wrote in the American Journal of Science and Art, “the highest effect of the sun’s rays . . . to be in carbonic acid gas,” and later declared, “an atmosphere of that gas [carbon dioxide] would give to our earth a high temperature.” Despite being the first to reach this conclusion, and despite the publication and initial promotion of her work, she was ultimately forgotten to history. That is, until 2011, when Raymond Sorenson, a retired geologist, rediscovered her work in an old almanac and recognized her importance. Since then, historians, scientists, and the public have done incredible work bringing her story to light. I am lucky enough to be one of them.

[Here is the article I wrote about her for Physics Today

Because there is no known photograph of Foote, we rely on artist illustrations such as this action shot of a woman scientist by Carlyn Iverson.

Carlyn Iverson

I first learned about Eunice Foote from a list of physicists from underrepresented groups compiled by AIP’s Assistant Public Historian, Joanna Behrman. At the time, I was an intern for the Center for History of Physics and Niels Bohr Library & Archives working to make K-12 teaching guides. I thought: “a woman in climate science whose contributions had been ignored for 150 years?” I was eager to learn more. However, there weren’t many resources available. Not even a known photograph of Eunice Foote, which is odd considering she was part of a well connected family and other family members had portraits. Interestingly enough, she was an artist herself, known for her landscapes.

She was not only a scientist and artist, but she was also a women’s suffrage activist. She and her husband attended the 1848 Seneca Falls convention which many credit with sparking the movement for women’s right to vote. She not only attended this momentous event, but served on the committee tasked with recording and publishing the meeting minutes, indicating she was among the leaders of this movement.

Eunice Foote is listed as an attendee alongside Cady Stanton.

Credit: Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection.

To add to this impressive list of occupations, she was also an inventor with a few patents to her name. It is also suspected that she assisted her husband, Elisha Foote, a patent judge, with some of his inventions.

One of Foote’s inventions was this shoe sole filler which minimizes squeaking. There is absolutely a pun about Foote and shoes waiting to be made. https://patents.google.com/patent/US28265A/en

After researching enough to make the teaching guides, I decided I was not ready to stop sharing her story so I pitched it to Physics Today. The journey to writing that article was unlike anything I had experienced before. With the confidence of such an impressive editorial staff supporting me, I reached out to experts–and they responded! I was intimidated by the prospect of impressing the very people who taught me everything I knew about Eunice Foote. It turns out the experts were just as eager to share their knowledge with me as I was to absorb it. I had never dived into a subject so deeply. I learned everything I could about that period in American history. For example, I talked with an expert in Puritanism to understand why New England was such a ripe place for learning in the mid-nineteenth century. One of the most gratifying exchanges I had was with a distant relative of Elisha Foote, Liz Foote (@footesea

Still, three teaching guides

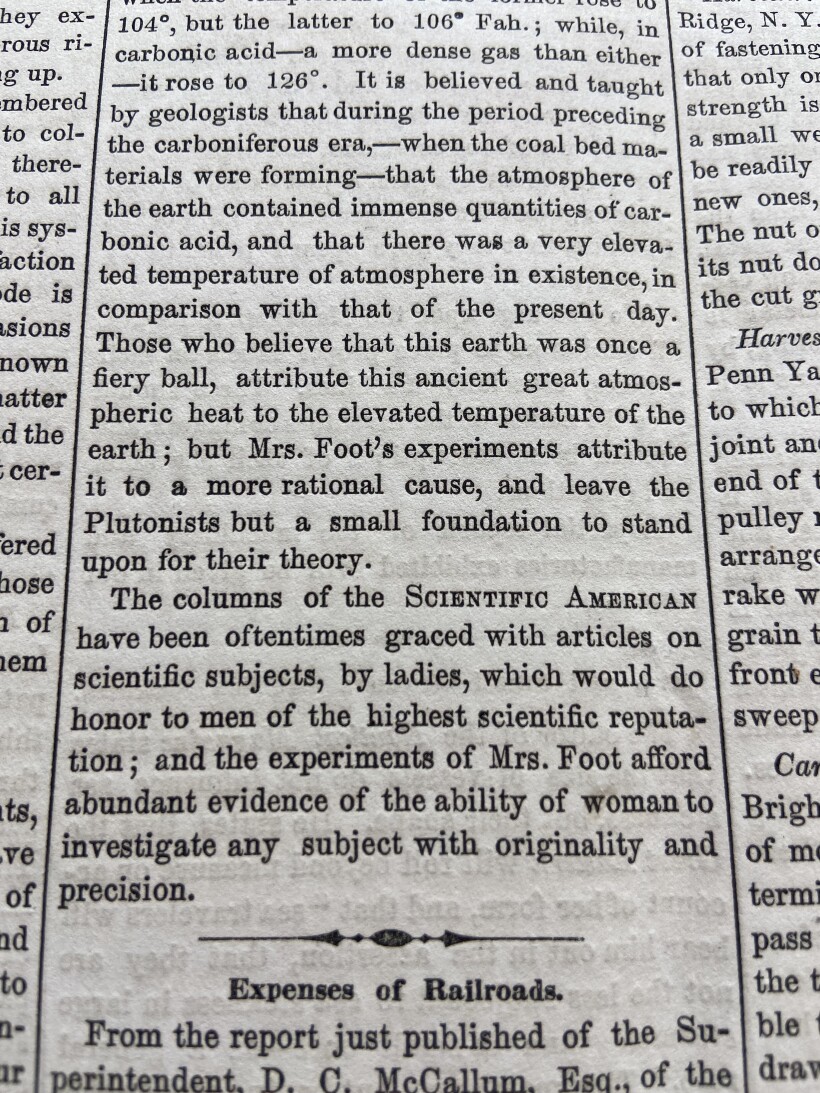

This issue of Scientific American demonstrated that Foote’s name did not have to slip into obscurity. In this 1857 issue, they praised Foote’s work and the work of women scientists.

AIP

Perhaps equally significant, this article said that by conducting this wondrous and important experiment, Eunice Foote proved women are talented scientists and that Scientific American benefited from their contributions. When commiserating on how women’s scientific achievements have been historically overlooked, it is easy, I think, to say, “oh well that was the past and maybe people just did not listen to women scientists.” This Scientific American article demonstrates that people could listen. The article concluded, “The columns of Scientific American have been tentimes graced with articles on scientific subjects, by ladies, who would do honor to men of the highest scientific reputation; and the experiments of Ms. Foot[e] afford abundant evidence to the ability of women to investigate any subject with originality and precision.”

The final paragraph is revealing of the clarity that some institutions had regarding women scientists: that women are as talented and valuable as men.

AIP

Instead of Eunice Foote receiving the credit for this conclusion, an Irish physicist, John Tyndall (approximately 1820-1883) was forever remembered as the discoverer of the greenhouse effect. This is where things get a little complicated. John Tyndall was the first person to discover the greenhouse effect. This is because the mechanism for heating the gasses in Foote’s experiment is slightly muddled and unaccounted for. The greenhouse effect is caused by gasses absorbing the infrared radiation (which we know as heat) that radiates off Earth’s surface. Eunice Foote likely measured a combination of direct sunlight and heat radiating off her glass jars to warm the gasses, therefore not the greenhouse effect. John Tyndall purposely measured the impact of infrared radiation on gasses and therefore discovered the greenhouse effect. Still, Foote was the first published scientist to conclude that carbon dioxide and water vapor absorb heat and that increasing carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere could cause global warming.

John Tyndall and Eunice Foote didn’t exactly start on equal foot[e]-ing. (That was a cheap pun, I know). While Eunice Foote was a highly educated woman for the 19th century United States, her background was no match for Tyndall’s. Being a European man, the scientific establishment was more accessible to him. He attended the University of Marburg and studied under and alongside some of the most prominent scientists of his time. When he decided to study how heat is absorbed by gasses, he had a team build a high precision device made to his specifications. There is also the mystery of whether or not he knew about Foote’s work, which preceded the publication of his own by three years. In this podcast episode, we dive into the drama surrounding this question.

Here is John Tyndall posing with his scientific friends and their impressively high tech instruments. This image was teased in May’s Photos of the Month post. In this circa 1865 portrait, he poses with (from left) Michael Faraday, Thomas Huxley, Charles Wheatstone, and David Brewster.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Zeleny Collection. Catalog ID Faraday Michael D2

At the end of the episode (I don’t think this spoils too much), Justin asks me why Eunice Foote’s story is so important to me. Eunice Foote was a woman who was ultimately underestimated despite all her work, talent, and privilege. I think many women in physics sometimes feel like we have to do more than our male counterparts for equivalent recognition and Foote’s story is an obvious example of this. Even though she was published in a scientific journal and her work was presented at the AAAS meeting, her contribution to atmospheric science was still forgotten. But, her story is also one of inspiration. Today, Eunice Foote’s name and work are receiving the attention they deserve because of the work of scientists, historians, and everyone who shares her story. It is thanks to you, our audience, who want to learn about the untold stories in physics and understand why they have not been told. That is what Initial Conditions: A Physics History Podcast is for: sharing the unconventional stories of physical discoveries and their context.

You can listen to Initial Conditions: A Physics History Podcast wherever you get your podcasts. A new episode will be released every Thursday so be sure to subscribe! On our website

Huddleston, Amara. “Happy 200th Birthday to Eunice Foote, Hidden Climate Science Pioneer.” Happy 200th birthday to Eunice Foote, hidden climate science pioneer | NOAA Climate.gov, July 17, 2019.

Jackson, Roland. “Eunice Foote, John Tyndall and a Question of Priority.” Notes and Records: the Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 74, no. 1 (2019): 105–18.

Ortiz, Joseph D., and Roland Jackson. “Understanding Eunice Foote’s 1856 Experiments: Heat Absorption by Atmospheric Gases.” Notes and Records: the Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 76, no. 1 (2020): 67–84.

Shapiro, Maura. “Eunice Newton Foote’s Nearly Forgotten Discovery.” Physics Today, August 23, 2021.

Sorenson, Raymond. “Eunice Foote’s Pioneering Research On CO2 And Climate Warming.” Search and Discovery, January 31, 2011.

Waxman, Olivia B., and Arpita Aneja. “The History of Seneca Falls You Didn’t Learn in School.” Time. Time, December 8, 2020.

Subscribe to Ex Libris Universum

Catch up with the latest from AIP History and the Niels Bohr Library & Archives.

One email per month